Understanding Cellular, Acellular, and Matrix-like Products (CAMPs) in Wound Healing

Learn what CAMPs are in wound care—cellular, acellular, and matrix-like products that support chronic wound healing and tissue regeneration.

admin

11/5/20257 min read

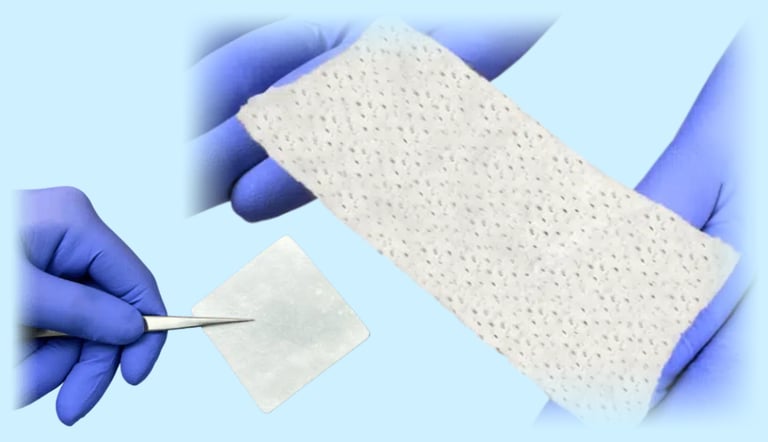

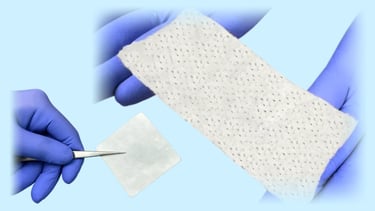

In modern wound care, advanced therapies have moved beyond simple dressings and basic gauze. Among these, a growing category known as cellular, acellular and matrix-like products (CAMPs) is gaining attention for their role in healing difficult or chronic wounds. These products (sometimes called skin substitutes, biologic scaffolds, or tissue-engineered matrices) are adjuncts to standard wound care and may help accelerate healing when foundational interventions alone aren’t enough.

In this guide we’ll explain what CAMPs are, break down the differences between cellular, acellular and matrix-like formulations, review the evidence for their use in clinical practice (especially for diabetic foot ulcers [DFUs], venous leg ulcers [VLUs] and pressure injuries), and offer practical considerations for clinicians selecting and using them in wound-care programs.

It’s important to note upfront: while evidence supports beneficial outcomes in many studies, CAMPs are not a guarantee of healing and must be used within a strong foundation of wound bed preparation, off-loading, infection control and perfusion optimization.

What are CAMPs? Definitions and categories

The term CAMPs has emerged to provide more clarity around the many advanced therapies now available. The consensus document from the Journal of Wound Care (JWC) describes CAMPs as products that can support and actively participate in tissue repair by providing scaffold architecture, bioactive molecules and, in some cases, viable or non-viable cells.

Here’s a practical way to think about the three main categories:

Cellular products: These contain living or viable cells (e.g. mesenchymal stem cells, fibroblasts, keratinocytes, amniotic-derived cells) applied to the wound bed. The idea is that these cells release growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular matrix (ECM) components to drive tissue regeneration. They act as biologic “factories”.

Acellular products: These contain no living cells but retain ECM architecture and some bioactive molecules (e.g. collagen matrices, decellularized dermal scaffolds, placental membranes). They provide a structure/scaffold for host cells to migrate, proliferate and rebuild tissue.

Matrix-like products: These may be synthetic or biologic scaffolds engineered to mimic the native ECM, sometimes combining collagen, glycosaminoglycans, elastin, hyaluronic acid, or synthetic polymers. The goal is to create the optimal microenvironment for wound healing.

Throughout the rest of this post, we’ll use the umbrella term “CAMPs” for ease of discussion, remembering that “cellular”, “acellular” and “matrix-like” each have distinct features.

Why are CAMPs important in wound care?

Chronic wounds (DFUs, VLUs, pressure injuries) often stall in healing because of multiple barriers: prolonged inflammation, elevated protease activity, impaired perfusion, biofilm infection, and degraded ECM. Standard wound care (debridement, off-loading, compression, infection control) remains essential, but sometimes it isn’t enough.

CAMPs aim to enhance the wound-healing microenvironment by providing:

A scaffold for tissue growth and neovascularization

Biological signaling (in cellular products) or preserved ECM cues (in acellular/matrix-like)

Protection from degradation and mechanical support

A platform for advanced therapies when used adjunctively to standard of care (SOC)

Evidence is growing. For example, a systematic review found that adjunctive use of CAMPs in DFUs resulted in a risk-ratio of ~1.72 (95% CI 1.56–1.90, p<0.00001) for wound closure compared with SOC alone. That's a 72% higher likelihood of healing! Another recent meta-analysis reported that patients treated with CAMPs were almost three times more likely to achieve full wound closure than those under SOC only. Similarly, real-world data in pressure ulcers suggested a ~16-percentage-point improvement when CAMPs were used.

These outcomes make CAMPs a meaningful part of advanced wound-care strategies; but they also require careful patient selection, timing, and integration into a broader wound-care protocol.

When and how to use CAMPs: Clinical considerations

Timing and wound bed preparation

Before applying a CAMP product, the wound bed should be optimized: necrotic tissue removed (debridement), infection treated or controlled, perfusion assessed, off-loading or compression in place, moisture balance ensured. If these foundations are not firmly established, even a sophisticated matrix may fail to integrate or result in poor outcomes. The JWC consensus emphasizes use of CAMPs when the wound remains stagnant despite foundational care.

Selecting the type of product

The choice between cellular, acellular and matrix-like depends on multiple factors:

Wound type and chronicity: more advanced, stalled wounds may benefit from cellular products; earlier stage or less refractory wounds may do well with acellular or matrix-like scaffolds.

Patient comorbidities and biology: if perfusion is marginal or infection unresolved, a scaffold alone may not succeed.

Cost and reimbursement: cellular products often cost more and may have stricter coverage criteria; acellular/matrix-like may be more accessible.

Evidence base: not all products have equivalent RCT data; clinicians should review head-to-head and real-world studies.

Application and follow-up

Proper application is critical:

After debridement, the product is placed in contact with clean granulating tissue or well-prepared wound bed.

Dressing type, fixation method, and off-loading/compression should be compatible with the product’s requirements.

Monitor healing progress: wound area reduction, granulation quality, exudate changes. Lack of improvement by 2–4 weeks may warrant reconsideration of the strategy or product used.

Document product details (size, lot, placement date), wound measurements, and outcome metrics.

Cost-effectiveness and resource allocation

While many studies show improved closure rates, cost-effectiveness remains variable. Clinics and providers should track outcomes (healing time, number of visits, need for advanced care or amputation) and compare the incremental cost per healed wound when using CAMPs. One review reported favorable cost outcomes when advanced products reduced overall care duration and complications.

Challenges and limitations

Despite their promise, CAMPs face several hurdles:

Heterogeneity in product definitions and study designs: It remains difficult to compare cellular vs acellular vs matrix-like head-to-head in many RCTs.

Reimbursement variability: Coverage criteria differ across payers and jurisdictions; access may be constrained.

Biology and patient variability: If infection, ischemia, uncontrolled diabetes or off-loading are not addressed, even the best product may fail.

Timing and placement errors: If the product is applied too early, on necrotic tissue, or without adequate fixation/off-loading, integration may fail.

Cost: Some cellular products remain expensive and may not be cost-effective in all clinics or patient populations.

Practical workflow for clinics using CAMPs

Step 1 – Identify candidates

Target wounds that are non-healing (e.g. minimal area reduction after 4 weeks of SOC), with adequate perfusion, controlled infection, and appropriate patient compliance (off-loading, compression, nutrition).

Step 2 – Select product type

Match wound and patient factors with product category:

Cellular for advanced non-healing wounds

Acellular or matrix-like for earlier or moderate refractory wounds

Step 3 – Optimise wound bed

Ensure thorough debridement, infection control, perfusion assessment, moisture balance, and adhesion of cells/scaffold.

Step 4 – Apply product and adjunctive therapy

Place CAMP per manufacturer instructions, ensure compatible dressing/off-loading, and integrate into broader plan.

Step 5 – Monitor outcomes and escalate

Track wound size, granulation quality, exudate levels. If no meaningful improvement by 2–4 weeks, reassess underlying barriers (ischemia, biofilm, nutrition) and consider alternative advanced therapies.

Step 6 – Document and review outcomes

Carefully document product used, wound metrics, patient compliance, and outcomes (healed vs stalled). Use this data for internal review, cost-effectiveness and payer conversations.

Case example (hypothetical)

A 62-year-old patient with diabetes, neuropathy and a 12-week non-healing plantar diabetic foot ulcer shows only 5% area reduction despite debridement, off-loading and standard dressings. Perfusion is adequate (toe pressure 65 mmHg). The clinic opts for a cellular product (allogeneic MSC-derived scaffold) plus off-loading boot and compression. After 2 weeks, granulation tissue improves and by 8 weeks the wound closes. Without the cellular scaffold the wound may have remained stalled longer, leading to higher risk of infection or amputation. The clinic documents all steps, compares cost of CAMP + visits vs extended SOC → demonstrates reduced total care cost.

Summary & key takeaway

CAMPs (cellular, acellular and matrix-like products) represent a powerful adjunct in advanced wound care. They offer scaffolding, cellular signaling and regeneration support beyond what traditional dressings provide. Evidence from RCTs and real-world studies indicates improved healing outcomes in chronic wounds when added to standard of care. But they are not a substitute for foundational wound management, and their success depends on patient selection, wound bed preparation, off-loading/compression, infection and perfusion control, and careful follow-up. For clinicians, understanding each product category, matching the correct product to the right wound and tracking outcomes and costs are essential to integrating CAMPs effectively in wound-care protocols.

See also

Best Practices for Chronic Wound Care: How to Assess Foot Ulcers Effectively

How to Tell If a Wound Is Healing: Signs of Proper Wound Care Progress

Why Diabetic Foot Wounds Heal Slowly: Top Factors That Delay Recovery

How Often Should Wound Dressings Be Changed? Best Practices for Healing

Wound Care Guide: How to Tell Colonization from True Infection

More Information

For more information on the latest effective wound care, contact us to set up a time for a call.

Sources

Wu S, Carter M, Cole W, et al. Best practice for wound repair and regeneration: use of cellular, acellular and matrix-like products (CAMPs). Journal of Wound Care. 2023;32(Sup4b):S1-31. https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/10.12968/jowc.2023.32.Sup4b.S1

https://www.journalofwoundcare.com/docs/JWC-CAMPs-Consensus_25-02-21.pdfBanerjee J, Lasiter A, Nherera L. Systematic Review of Cellular, Acellular, and Matrix-like Products and Indirect Treatment Comparison Between Cellular/Acellular and Amniotic/Nonamniotic Grafts in the Management of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2024 Dec;13(12):639-651. doi: 10.1089/wound.2023.0075. Epub 2024 Jul 10. PMID: 38780758. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38780758/

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/wound.2023.0075Weiying Lu, Min Hu, Zheng Zhang, John Slaughter, Anil Hingorani, Alisha Oropallo,

Meta-analysis of cellular and acellular tissue-based products demonstrates improvement of diabetic foot ulcer healing despite age and wound size, JVS-Vascular Insights, Volume 3, 2025, 100215, ISSN 2949-9127,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvsvi.2025.100215

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2949912725000327

Mulder G, Lavery LA, Marston WA, et al. Skin substitutes for the management of hard-to-heal wounds. Wounds International. 2024. https://woundsinternational.com/consensus-documents/skin-substitutes-for-the-management-of-hard-to-heal-wounds/

Tunyiswa Z, Dirks R, Walthall H. Real-world evaluation of cellular, acellular and matrix-like products (CAMPs) for pressure ulcers in post-acute settings. International Journal of Tissue Repair. 2025. https://doi.org/10.63676/kxwpnj30

https://internationaljournaloftissuerepair.com/index.php/ijtr/article/view/28Hughes OB, Rakosi A, Macquhae F, Herskovitz I, Fox JD, Kirsner RS. A Review of Cellular and Acellular Matrix Products: Indications, Techniques, and Outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016 Sep;138(3 Suppl):138S-147S. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002643. PMID: 27556754. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27556754/

https://journals.lww.com/plasreconsurg/abstract/2016/09001/a_review_of_cellular_and_acellular_matrix.19.aspxWilcox J. Vizient Inc. How cellular, acellular and matrix-like products (formerly known as CTPs) improve wound care. Vizient Blog. 2024. https://www.vizientinc.com/newsroom/blogs/2024/how-cellular-acellular-and-matrix-like-products-formerly-known-as-ctps-improve-wound-care

* This blog is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.