Wound Care Guide: How to Tell Colonization from True Infection

Learn how to distinguish wound colonization from true infection with clear signs, diagnostics, and wound care best practices to support healing.

admin

10/15/20256 min read

Distinguishing wound colonization from true infection is one of the most important and sometimes frustrating tasks in wound care. The difference matters: colonized wounds have microbes present but may still progress toward healing, while infected wounds show host response and tissue damage that usually require targeted treatment (local care, systemic antibiotics, or surgery). This guide explains practical, evidence-informed ways to tell the two apart, how to combine clinical signs with diagnostics, and how to act without overusing antibiotics.

The clinical problem: why the distinction matters

Bacteria are commonly present in wounds (contamination or colonization) but are not always causing harm. Treating colonization as if it were infection can lead to unnecessary antibiotics and resistance. Conversely, missing a true infection can delay healing and increase the risk of complications such as deeper tissue infection or limb loss, especially in high-risk situations like diabetic foot ulcers or immunocompromised patients. Leading consensus documents therefore stress a holistic clinical approach that combines signs and symptoms with appropriate diagnostics.

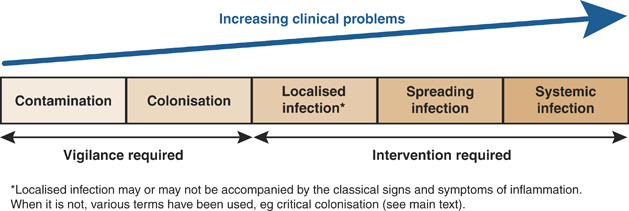

Understand the continuum: contamination → colonization → critical colonization → infection

Wounds are often described on a continuum:

Contamination: microbes present but transient and not multiplying.

Colonization: microbes present and multiplying but not eliciting a harmful host response; the wound may still progress toward healing.

Critical colonization (or heightened bioburden): a debated, intermediate state where microbial load and local effects impair healing but classic infection signs may be absent.

Infection: microbes are present and causing local tissue damage and usually inflammation; systemic signs may appear in severe cases.

This framework (the wound infection continuum) can help guide management but should not replace careful clinical assessment. Consensus groups emphasize that the intermediate term “critical colonization” has variable definitions and should be used with caution; instead, look for objective signs of impaired healing and host response.

Key clinical differences: what to look for at the bedside

No single sign is perfectly sensitive or specific. Use patterns.

Signs more consistent with colonization

Bacteria visible on superficial swab but no surrounding erythema, induration, or increased pain.

Wound shows gradual, slow healing but without acute worsening.

No systemic features (fever, tachycardia, lethargy).

Exudate may be present but not purulent or malodorous, or a chronic thin serous drainage without acute change.

In colonization, the priority is wound bed preparation (debridement, moisture balance, offloading, nutrition) and close monitoring rather than immediate systemic antibiotics.

Signs more suggestive of true local infection

New or increasing erythema, warmth, tenderness, and induration spreading beyond the wound margin.

Purulent drainage, new malodor, or increased exudate compared with baseline.

Delayed or deteriorating wound bed with necrosis despite optimized care.

Probe-to-bone positive in suspected diabetic foot infections (raises concern for osteomyelitis).

In severe cases: systemic signs such as fever, leukocytosis, hypotension — these indicate invasive or systemic infection requiring urgent care.

International consensus recommends classifying infection severity (mild, moderate, severe) and treating based on severity and host status.

The role of biofilm and why it complicates the picture

Biofilm (communities of bacteria encased in a protective matrix) commonly exists on chronic wounds and can impair healing without producing classic acute infection signs. Biofilm increases tolerance to antimicrobials and often requires mechanical disruption (debridement) along with targeted strategies. Recognizing biofilm-related delayed healing is part of modern wound assessment, but detection is not straightforward in routine practice. Clinicians should suspect biofilm when a wound has a stagnant or stalled healing trajectory despite appropriate care.

Practical assessment: a stepwise approach

History and trends

Ask about onset and pattern (new worsening vs chronic slow healing). Review recent interventions (antibiotics, dressing changes, offloading). A previously stable wound that acutely worsens suggests infection.

Focused clinical exam

Inspect for local signs (erythema, swelling, induration, warmth). Gently palpate for tenderness and check for crepitus, sinus tracts, or exposed bone. Evaluate periwound skin. Document size and photograph for serial comparison.

Assess systemic status

Look for fever, tachycardia, hypotension, or lab abnormalities (WBC, CRP) especially in patients with diabetes, peripheral vascular disease, or immunosuppression. Systemic signs raise the index of suspicion for invasive infection.

Use probe-to-bone and bedside tests judiciously

Probe-to-bone (PTB) is a simple clinical test in diabetic foot ulcers: a positive test increases the probability of osteomyelitis, but it’s not definitive; follow with imaging and bone culture as needed.

Sampling and diagnostics

When cultures are needed (suspected infection or non-healing wound despite care): obtain deep tissue or bone samples after debridement (not superficial swabs when possible) to guide therapy. Molecular diagnostics and quantitative techniques exist but are not yet standard everywhere. Combine microbiology results with clinical picture — presence of bacteria on culture alone does not prove infection.

Imaging if indicated

Plain X-ray for bone involvement; MRI is more sensitive for early osteomyelitis or deep tissue abscess. Imaging findings must be interpreted alongside clinical signs and labs.

When to treat with antimicrobials (practical rules)

Treat infection (local/systemic) when clinical signs indicate invasive infection — do not rely solely on swab cultures. Use targeted antibiotics guided by culture where possible. For severe or systemic infections, hospitalize and consult relevant specialists.

Avoid routine systemic antibiotics for colonization. Instead, optimize local wound care (debridement, moisture balance, dressings that manage exudate, biofilm disruption) and reassess. Topical antimicrobial dressings may be useful short-term in some contexts but should be part of a broader plan.

Reassess frequently. If a wound labeled “colonized” shows new clinical deterioration, shift to infection workup and treat accordingly.

Special situations and high-risk scenarios

Certain contexts lower the threshold for treating or investigating infection:

Diabetic foot ulcers or suspected osteomyelitis (use probe-to-bone, imaging, bone culture).

Immunocompromised patients (neutropenia, immunosuppressants) — infections may present atypically and progress rapidly.

Burns, large traumatic wounds, or surgical wounds with systemic signs — early aggressive treatment is often indicated.

In these cases, involve multidisciplinary teams early (wound care, infectious disease, surgery, vascular/podiatry as applicable).

Diagnostics: what’s useful and what’s not

Superficial swabs: convenient but limited — they often reflect surface contaminants and correlate poorly with deeper infection. Prefer deep tissue or bone cultures obtained after sharp debridement for guiding systemic therapy.

Quantitative cultures, molecular methods (PCR, sequencing): promising, but clinical interpretation and accessibility vary. Integrate results with clinical assessment rather than using them alone.

Biomarkers (CRP, procalcitonin): may help assess systemic infection but are not definitive for local wound infection.

Practical treatment principles when infection is confirmed

Debride devitalized tissue and disrupt biofilm. Mechanical removal is often the most important first step.

Obtain appropriate cultures (deep tissue/bone) before starting antibiotics, if clinically safe.

Start empiric antibiotics when clinically necessary, then narrow therapy according to culture and sensitivity (antimicrobial stewardship).

Address host factors — perfusion, glycemic control, nutrition, offloading — because these strongly affect outcomes.

Escalate care when necessary (surgery for abscess, debridement for necrosis, vascular surgery for ischemia).

Summary: a clinician’s cheat-sheet

Colonization = bacteria present without harmful host response; manage locally and monitor.

Infection = host response with tissue damage or systemic involvement; requires targeted therapy.

Use clinical signs first (erythema, warmth, tenderness, spreading induration, purulence, systemic features).

Prefer deep tissue or bone culture obtained after debridement for microbiology guidance.

Think biofilm when wounds stall despite good care; prioritize mechanical disruption.

Reserve systemic antibiotics for true infection and use culture-guided therapy where possible.

In high-risk patients (diabetes, immunosuppression, suspected osteomyelitis) act earlier and involve specialists.

Limitations

Evidence on the diagnostic thresholds that definitively separate colonization from infection is imperfect. Many recommendations come from expert consensus, observational studies, and diagnostic reviews rather than a single definitive test. Always integrate clinical judgment, the patient’s context, and multidisciplinary input. The approach above follows international consensus and recent reviews but is intentionally cautious rather than absolute.

See also

How to Tell If a Wound Is Healing: Signs of Proper Wound Care Progress

Best Practices for Chronic Wound Care: How to Assess Foot Ulcers Effectively

Why Diabetic Foot Wounds Heal Slowly: Top Factors That Delay Recovery

How Often Should Wound Dressings Be Changed? Best Practices for Healing

Best Wound Dressings for High-Exudate Wounds

More Information

For more information on the latest effective wound care, contact us to set up a time for a call.

Sources

Li S, et al. 2021. Diagnostics for Wound Infections. Pubmed Central

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8082727/Swanson T, et al. 2016. Wound Infection in Clinical Practice. International Wound Infection Institute (IWII)

https://woundinfection-institute.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/IWII-Consensus_Final-2017.pdfLipsky BA, et al. 2012. 2012 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases / Oxford Academic

https://academic.oup.com/cid/article/54/12/e132/455959Carville K, et al. 2008. Wound Infection in Clinical Practice. International Wound Journal, 5: iii-11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-481X.2008.00488.x

IWGDF/IDSA Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetes-related Foot Infections. International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF/IDSA 2023), Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2023;, ciad527, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad527

https://academic.oup.com/cid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/cid/ciad527/7287196Gottrup, F., Apelqvist, J., Bjansholt, T. et al. EWMA Document: Antimicrobials and Non-healing Wounds—Evidence, Controversies and Suggestions. Journal of Wound Care. 2013; 22 (5 Suppl.): S1–S92.

https://ewma.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/JWC-EWMA-supplement-NO-CROPS.pdfAbdul R. Siddiqui, Jack M. Bernstein. Chronic wound infection: Facts and controversies. Clinics in Dermatology, Volume 28, Issue 5, 2010, Pages 519-526, ISSN 0738-081X

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.009.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0738081X10000337Yi-Fan Liu, Peng-Wen Ni, Yao Huang, Ting Xie. Therapeutic strategies for chronic wound infection. Chinese Journal of Traumatology, Volume 25, Issue 1, 2022, Pages 11-16, ISSN 1008-1275,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjtee.2021.07.004.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1008127521001152IWII: Wound infection resources and practical tools. 2016 update. Wounds International.

https://woundsinternational.com/consensus-documents/iwii-wound-infection-clinical-practice/

* This blog is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.