When to Use Negative Pressure Wound Therapy: A Complete Guide

Discover when to use Negative Pressure Wound Therapy for optimal healing. Learn benefits, indications, and best practices for effective wound care.

admin

10/13/20257 min read

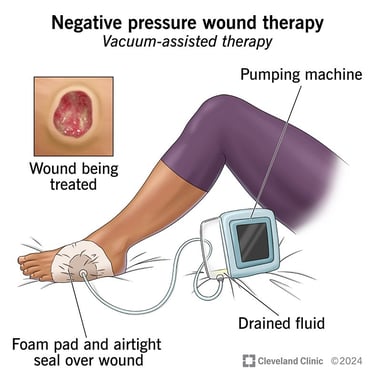

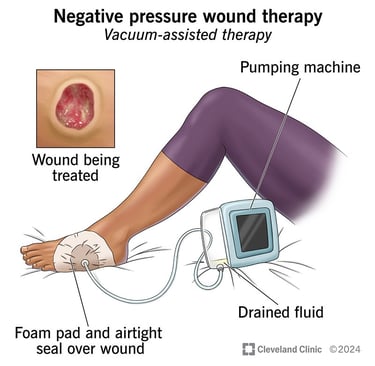

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT), often called a “wound vac,” is a widely used tool in modern wound care. It applies controlled suction to a wound through a sealed dressing and tubing connected to a pump. NPWT can remove exudate, reduce edema, support granulation tissue formation, help approximate wound edges, and sometimes lower bacterial burden. That said, NPWT is not a universal fix; proper patient selection, timing, and technique are essential. This guide explains when NPWT may be helpful, which wounds commonly benefit, clinical considerations and contraindications, practical setup and monitoring tips, and what the evidence and guidelines say.

Quick summary

NPWT can be helpful for complex, non-healing, or heavily exudating wounds, deep cavity wounds, some surgical incisions at high risk of dehiscence or infection, and to support skin grafts.

It is most effective as part of a comprehensive plan that addresses debridement, infection control, perfusion, offloading (for foot wounds), nutrition, and patient factors.

NPWT requires trained staff, correct dressing technique, and careful monitoring for complications (bleeding, retained foam fragments, periwound skin injury).

Evidence supports NPWT for selected indications (for example, improving wound bed for grafting or managing some pressure and diabetic foot wounds), but overall trial quality varies and clinical context matters. Guidelines recommend using NPWT selectively and re-evaluating progress.

What NPWT does (simple physiology)

NPWT applies sub-atmospheric pressure (usually set between roughly −50 mmHg and −125 mmHg depending on wound and system) through a porous dressing (foam or gauze) sealed with an occlusive drape. Benefits thought to contribute to healing include:

Removal of excess exudate and reduction of local edema.

Mechanical microdeformation of the wound surface, which may stimulate cell proliferation and granulation tissue formation.

Improved perfusion in the wound bed (in some settings).

Decreased frequency of dressing changes and protected wound environment.

These physiologic effects make NPWT attractive for deep, draining, or complex wounds, but each benefit may vary by wound type and patient.

Common clinical indications for NPWT

Below are frequently cited and guideline-supported situations where NPWT is commonly considered. This is not exhaustive; use clinical judgment.

1. Complex acute wounds and traumatic wounds (open/contaminated wounds)

NPWT is often used for temporary wound management after trauma (e.g., high-energy soft tissue injuries) to manage exudate, reduce edema, and prepare the wound prior to definitive closure or reconstruction. It can be used as a bridge to flap coverage in orthoplastic care. Evidence and reviews support its role as part of multidisciplinary trauma management.

2. Chronic non-healing wounds (pressure injuries, venous/diabetic foot ulcers)

For pressure ulcers and some diabetic foot ulcers, NPWT may accelerate reduction in wound size and improve the wound environment when combined with standard care (debridement, infection control, offloading/pressure redistribution). Systematic reviews suggest potential benefit in selected patients, with variable strength of evidence depending on wound etiology. Guidelines recommend NPWT as an option when conventional care is not progressing.

3. Skin grafts and biologic dressings

NPWT can be used to secure split-thickness skin grafts and help them “take” by removing seroma/hematoma under the graft and promoting close contact between graft and wound bed. Many surgeons use NPWT over grafts to improve graft adherence and early survival.

4. Dehisced or high-risk surgical wounds (including incisions at risk of infection)

Closed-incision NPWT (ciNPT) is increasingly used for prophylaxis on high-risk incisions (obese patients, vascular surgery, orthopedic/trauma incisions) to reduce seroma/hematoma and possibly lower infection risk. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses show mixed but promising results for selected high-risk surgeries; many guidance documents call for selective use rather than routine application.

5. Deep cavity wounds and tunneling wounds

NPWT is commonly used to manage cavity wounds (e.g., pilonidal sinus cavities, deep abscess cavities after drainage) because it can remove exudate and help collapse dead space. Instillation-capable NPWT (NPWTi-d), which periodically instills cleanser or antiseptic into the wound, has shown benefit in some orthoplastic and complex infected wounds.

When NPWT is less likely to be appropriate (relative contraindications)

Do not use NPWT without careful consideration in these situations, and consult specialists as needed:

Untreated osteomyelitis or uncontrolled deep infection — address infection first with debridement and systemic antibiotics (although NPWT may be used afterward or in select situations under specialist guidance).

Malignancy in the wound (active tumor at wound site) — NPWT is usually avoided in malignant wounds unless part of palliative care and specialist input supports use.

Exposed major blood vessels, organs, or anastomoses without vascularized tissue interposition — risk of bleeding or injury. Protective measures (nonadherent dressings or surgeons’ techniques) may mitigate risk in some settings.

Heavily bleeding wounds or coagulopathy — bleeding risk must be evaluated and controlled before NPWT.

Allergy to dressing materials or inability to achieve an effective seal.

These are not absolute rules. In complex cases, discuss risks/benefits with surgical or wound specialists.

How to select settings and dressings (practical notes)

Pressure settings: Common clinical ranges are −50 to −125 mmHg. Lower pressures may reduce pain but be less effective at fluid removal; higher pressures increase fluid removal but may increase discomfort or bleeding risk. Choose based on wound type, patient tolerance, and device instructions. Some wound types (fragile granulation, ischemic tissue) may require lower settings.

Mode: Continuous vs intermittent suction: intermittent modes may stimulate granulation more but can be less comfortable. Many clinicians use continuous suction initially and consider intermittent once tolerance and wound response are assessed.

Dressing type: Foam dressings (reticulated polyurethane) are common; gauze-based systems exist and can be preferable for narrow or irregular wounds. Ensure packing of cavities to avoid retained dressing fragments. Use interface layers or nonadherent contact layers when grafts or delicate structures are present.

Instillation (NPWTi-d): For contaminated or infected wounds, adding periodic instillation of saline or antiseptic (NPWTi-d) has shown improved outcomes in some studies versus NPWT alone. Consult evidence and product guidance.

Always follow manufacturer guidance, local protocols, and multidisciplinary recommendations.

Monitoring, complications, and when to stop

Monitoring is essential:

Daily checks for seal integrity, device alarms, canister output, periwound skin condition, pain, and signs of bleeding or infection. Teach patients using outpatient NPWT how to troubleshoot alarms and when to contact the clinic.

Complications to watch for: bleeding, retained foam fragments, maceration of periwound skin, periwound blistering, and increased pain. If severe bleeding or hemodynamic instability occurs, stop NPWT and seek urgent surgical review. Some reviews note skin blistering can be more common with NPWT than standard dressings.

Stopping criteria: adequate wound progress (granulation, reduced size/exudate) allowing conversion to simpler dressing, patient intolerance, or complications. Set a treatment review plan (for example, reassess every 1–2 weeks) and document progress.

Practical care pathways (examples)

Traumatic open wound awaiting closure: debride and irrigate → consider NPWT for temporary management to control exudate and support granulation → definitive closure or flap once wound bed optimized.

Diabetic foot ulcer with deep cavity and moderate exudate (no critical ischemia): ensure perfusion and offloading first → debride if necessary → consider NPWT if wound fails to progress with standard dressings or exhibits large cavity. Monitor closely for infection and bleeding.

High-risk surgical incision (obese patient): consider closed-incision NPWT to reduce seroma and possibly lower SSI risk, using devices designed for ciNPT, and monitor per local surgical protocols. Evidence supports selective use rather than routine use for all incisions.

What the evidence and guidelines say

Systematic reviews and Cochrane evidence find that NPWT may reduce wound area and possibly lower some complication rates for selected wounds (pressure ulcers, some surgical wounds), but the certainty of evidence is often low to moderate and study heterogeneity is substantial. Outcomes vary by wound type, patient group, and comparator care.

IWGDF (2023) and other specialty guidelines recommend NPWT as a considered option for diabetic foot ulcers and other complex wounds when used within multidisciplinary care pathways and after addressing perfusion, infection, and offloading.

NPWT with instillation (NPWTi-d) has shown added value for some infected or complex wounds in meta-analyses, but these technologies often require specialist oversight and more research to define ideal indications.

In short: NPWT can be an effective tool in the right patient and wound, but it should be used thoughtfully within broader wound-care strategies rather than as a first-line universal treatment.

Costs, outpatient use, and patient factors

NPWT devices and consumables carry cost and logistics implications. Many health systems use NPWT in outpatient settings with portable devices to reduce inpatient days. Reimbursement, device availability, home-care support, and patient ability to manage the device at home all influence whether NPWT is practical. When cost or access is a barrier, document rationale for NPWT and consider alternate evidence-based strategies.

Final checklist: is NPWT right for here and now?

Ask these questions before starting NPWT:

Has the wound been optimised (debrided, infection addressed, perfusion assessed, offloading or pressure relief in place)?

Is there a clear treatment goal (reduce cavity size, prepare graft bed, control exudate, support difficult closure)?

Can you safely seal the wound and avoid contact with exposed major vessels or organs?

Do you have staff trained to apply and monitor NPWT and a plan for outpatient support if needed?

Is the patient medically stable and informed about benefits, limitations, and potential complications?

If you can answer “yes” to most items, NPWT may be an appropriate option to consider. If not, address the gaps first or discuss with a wound/surgical specialist.

See also

How to Tell If a Wound Is Healing: Signs of Proper Wound Care Progress

Best Practices for Chronic Wound Care: How to Assess Foot Ulcers Effectively

Why Diabetic Foot Wounds Heal Slowly: Top Factors That Delay Recovery

How Often Should Wound Dressings Be Changed? Best Practices for Healing

Best Wound Dressings for High-Exudate Wounds

More Information

For more information on the latest effective wound care, contact us to set up a time for a call.

Sources

Zaver V, et al. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy. StatPearls (National Center for Biotechnology Information). 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576388/

Norman G, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy for surgical wounds healing by primary closure. Cochrane Library. 2022. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009261.pub7/full Cochrane Library

Chen P, et al. Guidelines on interventions to enhance healing of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes. International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF). 2023. https://iwgdfguidelines.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/IWGDF-2023-07-Wound-Healing-Guideline.pdf

Shi J, et al. NPWT for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Library. 2023. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011334.pub3/abstract

De Pellegrin L, et al. Effects of negative pressure wound therapy with instillation and dwell time (NPWTi-d) versus NPWT or standard of care in orthoplastic surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Wound Journal. (2023). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10333051/

O'Leary R, et al. Review report of MTG43: PICO negative pressure wound dressings for closed surgical incisions. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/mtg43/evidence/review-report-february-2024-pdf-13314467630

Al-Sabbagh L, et al. Effect of high negative pressure wound therapy in diabetic foot ulcer healing. Wounds International. 2020. https://woundsinternational.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/79354e41264648729aa82cba61d138db.pdf Wounds International

RENASYS and PICO NPTW Systems clinical guidelines: https://sn-npwtportal.com/sites/default/files/npwtPortal/EDGE/gettingStarted/NPCE9-42082-0125-NPWT%20Clinical%20Guidelines-FINAL%20APPROVED.pdf.

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy. United Healthcare Oxford Clinical Policy. 2025.

Negative Pressure Wound Therapy in the Outpatient Setting. BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee Medical Policy Manual. https://www.bcbst.com/mpmanual/Negative_Pressure_Wound_Therapy_in_the_Outpatient_Setting.htm

* This blog is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.