Why Offloading Is Critical in Wound Care — Best Devices for Healing

Learn why offloading is essential for wound healing. Explore top devices for diabetic foot ulcers and best practices for effective pressure relief.

admin

10/14/20257 min read

Offloading, the practice of reducing pressure and shear on a wound-bearing area, is one of the most important, evidence-based steps for treating many lower-extremity wounds, particularly diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs) and pressure injuries. When mechanical stress continues on an ulcer, even excellent dressings and antibiotics may not be enough. This guide explains why offloading matters, which devices clinicians commonly use, how to choose between options, practical tips to improve patient adherence, and when to escalate care.

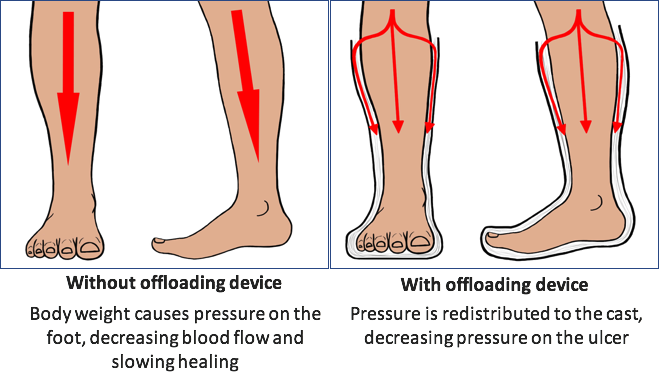

Why offloading matters (simple physiology)

Wounds heal when new tissue forms and stress on the tissue is minimized. On the plantar surface of the foot, repeated pressure and shear from weight-bearing and walking cause local tissue breakdown and prevent the wound bed from closing. Offloading reduces peak plantar pressures, prevents repetitive trauma, and creates a mechanical environment that allows granulation and re-epithelialization to proceed. International guidelines identify offloading as a primary intervention in treating neuropathic plantar ulcers in people with diabetes.

Put another way: dressings and antimicrobials treat the wound environment; offloading treats the cause: mechanical overload. Combining both approaches gives the best chance for wound closure.

What the major guidelines recommend

The International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF) strongly recommends a non-removable, knee-high offloading device (for example, a total contact cast or a non-removable walker cast) as the first choice to heal a neuropathic plantar forefoot or midfoot ulcer, when not contraindicated. If a non-removable device cannot be used, a removable knee-high offloading device is the next option, and a removable ankle-high device is a third choice. The recommendations are based on high-quality evidence and were updated in the 2023 guideline.

Key idea: non-removability improves effectiveness because patients may not wear removable devices consistently; locking the device in place eliminates this adherence barrier. Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses support superior healing with non-removable cast devices compared with removable walkers, therapeutic footwear, or conventional care.

The offloading options: strengths, limitations, and typical use

Below are the common offloading solutions you’ll encounter in clinics, with practical pros and cons.

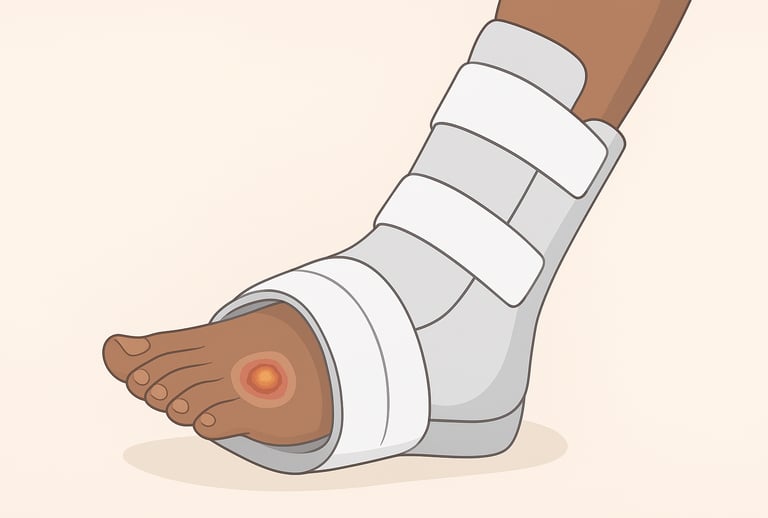

1. Total contact cast (TCC): the traditional “gold-standard”

What it is: A well-molded, circumferential, non-removable cast that evenly redistributes plantar pressures across the foot and lower leg.

Why clinicians use it: TCCs reduce peak plantar pressure effectively and are associated with faster healing and higher healing rates in many studies.

Limitations: Requires technical skill to apply, can make wound inspection harder (so frequent clinical review is needed), and it may be contraindicated with severe infection, critical ischemia, or unstable gangrene. Some studies note higher device-related complications (e.g., skin issues) when not applied or monitored correctly.

2. Non-removable walker cast (knee-high, non-removable)

What it is: A prefabricated walker or cast rendered non-removable (e.g., by wrapping or a secure cuff).

Why use it: Offers many of the benefits of TCC (pressure reduction and enforced adherence) and can be simpler to fit in some settings. The IWGDF counts these as an acceptable alternative to TCC based on resources and skills available.

3. Removable cast walkers (RCWs / “Cam walkers”)

What it is: A removable, rigid or semi-rigid boot that redistributes pressure but can be taken off by the patient.

Why use it: Easier to apply and inspect the wound; useful when non-removable devices are contraindicated or not tolerated.

Limitations: Less effective than non-removable options when patient adherence is poor. Studies show RCWs can heal ulcers but typically at slower rates if not worn consistently. Encourage patients to wear RCWs at all weight-bearing times.

4. Therapeutic footwear, custom insoles, and rocker soles

What they are: Shoes designed to redistribute pressure (rocker soles) and insoles or custom orthoses tailored to reduce focal loads.

Why use them: Useful for prevention, for offloading small or residual ulcers, and long-term management to reduce recurrence risk. Custom devices can reduce pressure effectively, but their performance varies with design and patient fit.

5. Felted foam, adhesive padding, and local offloading aids

What they are: Soft felt or foam padding adhered around a lesion to deflect pressure away from the wound.

Why use them: Low-tech, inexpensive option for plantar ulcers in specific anatomical locations. Can be used under shoes or in combination with other devices when applied correctly. Evidence supports benefit for pressure redistribution in some cases, especially when custom made.

6. Half-shoes, forefoot offloading shoes, and toe spacers

Use cases: Short-term offloading for forefoot ulcers when casting is not suitable. They reduce forefoot pressure but can change gait and require patient education.

7. Surgical offloading (tendon lengthening, osteotomies, percutaneous procedures)

When to consider: For recurrent ulcers caused by fixed deformities (hammer toes, rocker deformities) or when conservative offloading repeatedly fails. Surgical procedures can permanently reduce focal pressures but carry operative risks and require careful patient selection.

Evidence snapshot: what trials and reviews tell us

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews consistently show better healing with non-removable knee-high devices (TCC or non-removable walkers) versus removable devices or therapeutic shoes. However, the magnitude of benefit and complication rates vary across studies.

Randomized trials from the 2000s and later found that TCCs produced faster ulcer closure than half-shoes or RCWs in many settings, supporting guideline recommendations that rank non-removable devices first.

Newer studies and reviews continue to evaluate custom devices and adherence strategies; some recent trials suggest custom offloading and tailored devices may offer similar benefits where casting is not feasible. Evidence continues to evolve.

Takeaway: strong, consistent evidence supports non-removable knee-high offloading as a first-line option when feasible, but local expertise, patient preference, and comorbidities determine the practical choice.

Choosing the right device: a practical algorithm

Assess wound location and cause. Forefoot / plantar neuropathic ulcers commonly benefit from knee-high non-removable offloading. Heel or posterior wounds may need different approaches.

Check for contraindications. Severe infection, critical limb ischemia, unmanageable edema, or inability to inspect the wound may make non-removable devices unsafe. Treat infection/ischemia first.

Consider patient factors. Mobility, home support, risk of falls, work needs, and ability to attend follow-up matter. If adherence is unlikely, prioritize non-removable options when safe.

Start with the strongest feasible option. If no contraindication and staff skilled in application are available, use TCC or non-removable walker. If not feasible, use RCW with strict adherence strategies and education.

Combine offloading with best wound care. Offloading is not a stand-alone cure — pair it with debridement, infection control, vascular assessment, glycemic management, and appropriate dressings.

Improving adherence and reducing complications

Non-removable devices are effective partly because patients can’t remove them. But that strength also requires frequent clinic follow-up to monitor skin integrity, circulation, and device fit. For removable devices, interventions that improve adherence (education, reminders, mobile health checks) can improve outcomes. Choose devices that allow reasonable wound checks and address fall risk, hygiene, and patient comfort.

Common complications to watch for: new pressure areas, maceration, infection, device-related skin lesions, and falls if the device alters gait. Regular review and skilled application reduce these risks.

Practical tips for clinics and patients

Document baseline pressure points (use imaging or pressure mapping if available) and photograph wounds before offloading.

Schedule frequent review visits during the first 1–2 weeks after casting to check for new pressure sites, fit problems, and early healing.

Educate patients about the reason for offloading, expected wear time, and how to manage hygiene and mobility safely. For RCWs, emphasize “wear time” at all weight-bearing moments.

Combine offloading with prevention: once healed, use therapeutic footwear and custom insoles to reduce recurrence risk. Most recurrences happen within months to years without preventive strategies.

When to escalate care

Escalate to multidisciplinary teams or consider surgical offloading when: the wound fails to show expected progress after appropriate offloading and standard care, infection persists or deepens, perfusion is poor, or deformity causes recurrent focal pressure. Specialist input (vascular surgery, podiatry, orthopedics, wound care nurse) improves decision-making and outcomes.

Limitations and cautious language

No single offloading device is perfect for every patient and every wound. Study methods vary, and device choice should be individualized. While meta-analyses and guidelines strongly favor non-removable knee-high devices for many plantar neuropathic ulcers, clinicians must weigh benefits against risks and local practicalities.

Key takeaways

Offloading addresses the mechanical cause of many chronic lower-extremity wounds and is essential for healing neuropathic plantar ulcers.

Non-removable knee-high devices (TCC or non-removable walkers) are first-choice offloading options when safe and feasible. They tend to produce faster healing than removable devices and therapeutic shoes.

If non-removable devices are contraindicated, use removable knee-high walkers or ankle-high devices but prioritize improving adherence and frequent review.

Always combine offloading with standard wound care: debridement, infection control, vascular assessment, glycemic control, and proper dressings.

See also

How to Tell If a Wound Is Healing: Signs of Proper Wound Care Progress

Best Practices for Chronic Wound Care: How to Assess Foot Ulcers Effectively

Why Diabetic Foot Wounds Heal Slowly: Top Factors That Delay Recovery

How Often Should Wound Dressings Be Changed? Best Practices for Healing

Best Wound Dressings for High-Exudate Wounds

More Information

For more information on the latest effective wound care, contact us to set up a time for a call.

Sources

Bus S, et al. 2023. Guidelines on offloading foot ulcers in persons with diabetes. International Working Group on the Diabetic Foot (IWGDF).

https://iwgdfguidelines.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/IWGDF-2023-06-Offloading-Guideline.pdf.Li B, et al. 2023. Total contact casts versus removable offloading interventions for the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Endocrinology.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2023.1234761/fullArmstrong D, et al. 2001. Off-loading the diabetic foot wound: a randomized clinical trial. American Diabetes Association.

Elraiyah T, et al. 2016. Systematic review and meta-analysis of off-loading methods for diabetic foot ulcers. Journal of Vascular Surgery.

https://www.jvascsurg.org/article/S0741-5214(15)02028-5/pdf.

Messenger G, et al. 2018. A Narrative Review of the Benefits and Risks of Total Contact Casts in the Management of Diabetic Foot Ulcers. SceinceDirect.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S2213510318300344.Rumanes A, et al. 2025. Offloading Strategies Used for Plantar Diabetic Foot Ulcers and Their Outcomes in Real- Life Clinical Practice. Journal of Clinical Medicine.

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12156787/Jones, A.W., Makanjuola, A., Bray, N. et al. The efficacy of custom-made offloading devices for diabetic foot ulcer prevention: a systematic review. Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome. 16, 172 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-024-01392-y. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11267867/

Boulton AJM, et al. 2022. New evidence-based therapies for complex diabetic foot wounds. , American Diabetes Association.

https://diabetesjournals.org/compendia/article/2022/2/1/147002/New-Evidence-Based-Therapies-for-Complex-DiabeticOkoli GN, Rabbani R, Lam OLT, Askin N, Horsley T, Bayliss L, et al. Offloading devices for neuropathic foot ulcers in adult persons with type 1 or type 2 diabetes: a rapid review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care. 2022;10:e002822. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjdrc-2022-002822

Fletcher J, et al. 2024. Improving offloading for the foot in diabetes: Use of total contact casting in practice. Wounds UK.

https://wounds-uk.com/consensus-documents/improving-offloading-for-the-foot-in-diabetes-use-of-total-contact-casting-in-practice/Wu Y, et al. 2025. Comparison of the Effectiveness and Safety of Different Non-surgical Offloading Interventions for Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.

The International Journal of Lower Extremity Wounds.

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/15347346251329609

* This blog is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.