Peptides in Wound Healing: Past Lessons, Current Therapies, and Future Innovations for Chronic Wounds

Discover how peptides enhance wound healing—past, present, and future. Explore antimicrobial, growth, and matrix peptides transforming chronic care.

admin

11/7/20258 min read

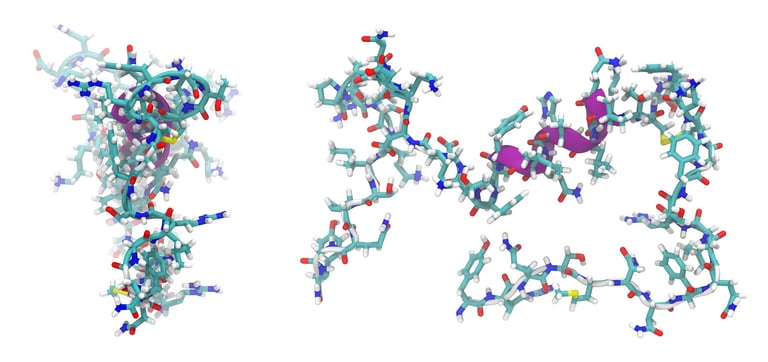

Peptides, short chains of amino acids, are versatile biological tools that can influence cell behavior, fight microbes, and guide tissue repair. Over the past few decades they have moved from laboratory curiosities to real wound-care products and are now the subject of intense research for next-generation dressings, hydrogels, and injectable therapies. This post explains what peptides do in wound healing, summarizes where peptide therapies have already been used, describes current clinical and real-world applications, and surveys promising directions that may appear in clinics in the years ahead.

Why peptides matter for wounds

Wound healing is a complex process that depends on inflammation control, infection management, cell migration, new blood-vessel growth, and rebuilding of the extracellular matrix (ECM). Peptides can participate in several of those steps:

Some peptides act like growth signals that tell cells to divide, migrate, or lay down new matrix.

Some are antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) that kill bacteria and help control biofilm.

Others are matrix-derived peptides that mimic ECM signals and encourage tissue remodeling.

Peptides can also be built into hydrogels, dressings, or scaffolds to provide sustained local action and mechanical support.

Because peptides are relatively small, they can be designed for specific functions, combined with biomaterials, and (in many cases) manufactured cost-effectively compared with whole proteins or living cell products.

The past: early peptide and growth-factor therapies

The first wave of peptide-related wound therapies in clinical practice were recombinant growth factors rather than short synthetic peptides. For example, becaplermin (recombinant human platelet-derived growth factor, rhPDGF-BB) was approved for diabetic foot ulcers and is probably the best-known example of a growth-factor therapy in wound care. Clinical trials showed that PDGF could accelerate closure in some patients, though adoption was tempered by cost, mixed trial results across settings, and safety/regulatory discussions.

At the same time, researchers discovered endogenous peptides with antimicrobial and immunomodulatory roles. The human peptide LL-37 (a cathelicidin) was identified as a key natural wound peptide that kills bacteria, disrupts biofilms, modulates inflammation, and promotes re-epithelialization in preclinical models. Early clinical phase studies and translational work with LL-37 derivatives showed promise for chronic wounds with significant microbial burden.

Those early experiences taught two important lessons: (1) delivering biologically active molecules to a hostile chronic wound environment is hard (proteases and biofilms degrade them), and (2) single-agent approaches may be insufficient unless the wound bed is optimized (debridement, perfusion, off-loading, infection control). These lessons inform current designs for peptide therapies.

The present: where peptides are used today

Modern peptide applications in wound care fall into several categories:

1. Growth-factor and growth-factor-derived peptides

Beyond full-length recombinant growth factors, short peptide fragments derived from growth factors or ECM proteins can mimic key signaling without some limitations of large proteins. These smaller molecules may be more stable and easier to deliver locally. Examples in research include PDGF-derived peptides and ECM-mimetic sequences that encourage fibroblast migration and angiogenesis. Clinical translation is active but variable by product.

2. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs)

AMPs, such as LL-37 or engineered LL-37 derivatives, show both antimicrobial and immune-modulating effects. They can reduce bacterial load and biofilm, and also promote wound closure by recruiting host cells and modulating inflammation. Several AMPs have progressed into early clinical trials or topical formulations aimed at chronic wounds and infected ulcers. Reviews in the last few years highlight AMPs as a promising strategy against resistant organisms and biofilms in wounds.

3. Matrix-derived and collagen-derived peptides

When the extracellular matrix breaks down, short peptides released from collagen and other proteins can act as signals to cells. Collagen-derived peptides and small tripeptides are used in dressings or topical formulations to exploit these signaling roles, and collagen dressings (which often include peptide fragments or hydrolyzed collagen) are widely used in clinical practice. Clinical evidence supports collagen dressings for improving wound bed quality and supporting healing in many chronic wound types.

4. Peptide-modified hydrogels and scaffolds

Peptide sequences, including cyclic and stabilized peptides, are incorporated into hydrogels or nanofibers to give materials bioactivity (e.g., encourage cell adhesion, reduce protease activity, or release antimicrobial peptides). Peptide-loaded hydrogels are a rapidly growing research area, with several promising preclinical and early-phase clinical studies showing improved re-epithelialization and angiogenesis in diabetic and chronic wound models.

5. Peptides as adjuvants to advanced therapies

When clinicians use skin substitutes, grafts, or cell therapies, peptides can be used to condition the wound bed or to protect grafts from protease degradation. For instance, peptide-containing dressings have been used to reduce local protease activity so that subsequent grafting is more likely to succeed.

What trials and reviews show

Becaplermin (PDGF): multiple randomized trials and meta-analyses showed improved rates of closure in some DFU populations, though effect size and adoption vary and cost is a consideration.

LL-37 and AMPs: phase I/II data and preclinical studies show that LL-37-based products can reduce bacterial burden and promote healing in chronic wounds; larger trials are ongoing or planned. Reviews underscore AMPs’ dual antimicrobial and immunomodulatory roles.

Peptide hydrogels and ECM peptides: strong preclinical data and small clinical series suggest improved tissue regeneration, re-epithelialization, and angiogenesis; larger randomized studies are needed for definitive practice change.

Overall, the evidence supports a role for peptide therapies in complex or refractory wounds, but conclusions about which product is best for which wound type still require more comparative trials.

Practical barriers and current limitations

Despite promise, peptide therapies face practical challenges:

Protease-rich wound environment. Chronic wounds often contain high protease activity that degrades peptides; successful peptide products must be delivered in formats that protect them (e.g., peptide-modified matrices or controlled-release hydrogels).

Stability and formulation. Peptides can be unstable in solution and may need stabilization (cyclization, PEGylation, encapsulation). Advances in peptide chemistry address many of these issues but add complexity.

Cost and reimbursement. Some peptide products or combination biologics are expensive. Payers may require evidence of cost-effectiveness compared with optimized standard care.

Regulatory complexity. Peptides can be regulated differently depending on whether they are classified as drugs, biologics, or device components, which affects trial design and approval pathways.

Heterogeneous evidence base. Studies vary in quality, wound type, and outcomes measured — making head-to-head comparisons hard.

These challenges are not insurmountable; they instead guide research toward robust delivery platforms, better patient selection, and combined approaches.

The future: where peptide research is heading

Several exciting directions could make peptides a mainstream part of wound care in coming years:

1. Smart peptide hydrogels and responsive dressings

Hydrogels that release peptides in response to local cues (pH, protease activity, temperature) can provide on-demand therapy and protect peptides until needed. Early research shows peptide-loaded responsive hydrogels accelerate diabetic wound closure in animal models.

2. Combinational peptide therapies

Combining AMPs with growth-promoting peptides, or packaging peptides with protease inhibitors and antioxidants, could address multiple barriers at once: reduce infection, dampen harmful proteases, and stimulate regeneration. Multifunctional peptide dressings could become a standard for complex wounds.

3. Engineered cyclic and peptidomimetic molecules

Cyclic peptides and peptidomimetics are more resistant to proteolysis, have improved tissue penetration, and can be fine-tuned for target specificity (e.g., angiogenesis vs. anti-inflammatory). These engineered peptides may provide more durable clinical effects with fewer doses.

4. Personalized peptide cocktails and predictive biomarkers

As wound diagnostics improve (protease tests, microbial profiling, perfusion markers), clinicians may tailor peptide choice and dose to the wound’s biochemical profile. For example, a protease-high, biofilm-positive wound might receive an AMP + protease-protective hydrogel, while a well-perfused stalled wound might receive a growth-signal peptide plus scaffold.

5. Peptides in regenerative scaffolds and cell therapies

Peptides can prime scaffolds to better integrate with host tissue or improve survival/function of grafted cells. Combined approaches (cells + peptide-rich matrices) could enhance outcomes for large or difficult wounds.

Practical advice for clinicians now

Don’t abandon fundamentals. Peptides are adjuncts; they typically work best after debridement, infection control, off-loading, and perfusion optimization.

Match product to wound biology. If a wound is heavily infected or protease-rich, pick formulations designed to protect peptides (hydrogels, matrix carriers) or consider AMPs.

Document and measure. When using peptide products, document wound size, timeline, infection status, perfusion and patient factors so you can evaluate effectiveness locally.

Watch for new evidence. Peptide research is fast moving; be ready to adopt high-quality innovations backed by randomized trials and cost-effectiveness data.

Bottom line

Peptides have moved from experimental tools to practical components of modern wound care. Growth-factor-derived peptides, antimicrobial peptides, matrix-mimetic sequences, and peptide-loaded hydrogels each play distinct roles in addressing the common barriers to healing in chronic wounds. The field continues to evolve: smarter delivery systems, engineered peptide chemistries, and combination strategies promise more reliable, targeted wound therapies in the near future. For clinicians, peptides represent another option in the toolbox, most powerful when used in well-prepared wounds and chosen to match the wound’s biological profile.

See also

When to Use Skin Substitutes or Grafts for Non-Healing Wounds

Stem Cells, Exosomes, and Biologics: Do They Work in Wound Care?

How to Tell If a Wound Is Healing: Signs of Proper Wound Care Progress

Why Diabetic Foot Wounds Heal Slowly: Top Factors That Delay Recovery

How Often Should Wound Dressings Be Changed? Best Practices for Healing

More Information

For more information on the latest effective wound care, contact us to set up a time for a call.

Sources

Deptuła M, Karpowicz P, Wardowska A, Sass P, Sosnowski P, Mieczkowska A, Filipowicz N, Dzierżyńska M, Sawicka J, Nowicka E, Langa P, Schumacher A, Cichorek M, Zieliński J, Kondej K, Kasprzykowski F, Czupryn A, Janus Ł, Mucha P, Skowron P, Piotrowski A, Sachadyn P, Rodziewicz-Motowidło S, Pikuła M. Development of a Peptide Derived from Platelet-Derived Growth Factor (PDGF-BB) into a Potential Drug Candidate for the Treatment of Wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2020 Dec;9(12):657-675. doi: 10.1089/wound.2019.1051. Epub 2019 Oct 29. PMID: 33124966; PMCID: PMC7698658. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7698658/

https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/10.1089/wound.2019.1051T. Jeffery Wieman, Clinical efficacy of becaplermin (rhPDGF-BB) gel, The American Journal of Surgery, Volume 176, Issue 2, Supplement 1, 1998, Pages 74S-79S, ISSN 0002-9610, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9610(98)00185-8

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0002961098001858

Duplantier AJ, van Hoek ML. The Human Cathelicidin Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 as a Potential Treatment for Polymicrobial Infected Wounds. Front Immunol. 2013 Jul 3;4:143. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00143. PMID: 23840194; PMCID: PMC3699762. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3699762/

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/immunology/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2013.00143/fullHaidari H, et al. Therapeutic potential of antimicrobial peptides for wound healing. American Journal of Physiology - Cell Physiology. 2023. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00080.2022 https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/ajpcell.00080.2022

Y. Xiao, L.A. Reis, N. Feric, E.J. Knee, J. Gu, S. Cao, C. Laschinger, C. Londono, J. Antolovich, A.P. McGuigan, & M. Radisic, Diabetic wound regeneration using peptide-modified hydrogels to target re-epithelialization, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 (40) E5792-E5801, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1612277113 (2016). https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1612277113

Nizam AAK, Masri S, Fadilah NIM, Maarof M, Fauzi MB. Current Insight of Peptide-Based Hydrogels for Chronic Wound Healing Applications: A Concise Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18010058. https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8247/18/1/58

Lee Y-CJ, Javdan B, Cowan A and Smith K (2023) More than skin deep: cyclic peptides as wound healing and cytoprotective compounds. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 11:1195600. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2023.1195600 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2023.1195600/full

Shubham Sharma, Vineet Kumar Rai, Raj K. Narang, Tanmay S. Markandeywar, Collagen-based formulations for wound healing: A literature review, Life Sciences, Volume 290, 2022, 120096, ISSN 0024-3205, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2021.120096.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0024320521010833

Shi, S., Wang, L., Song, C. et al. Recent progresses of collagen dressings for chronic skin wound healing. Collagen & Leather 5, 31 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42825-023-00136-4 https://jlse.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s42825-023-00136-4

Ana Gomes, Paula Gomes, Peptides and peptidomimetics in the development of hydrogels towards the treatment of diabetic wounds, Current Research in Biotechnology, Volume 9, 2025, 100292, ISSN 2590-2628,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbiot.2025.100292.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590262825000231

Cong, R., Deng, C., Li, P. et al. Dimeric copper peptide incorporated hydrogel for promoting diabetic wound healing. Nat Commun 16, 5797 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61141-1 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-61141-1

Mahdipour E, Sahebkar A. The Role of Recombinant Proteins and Growth Factors in the Management of Diabetic Foot Ulcers: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Diabetes Res. 2020 Jul 11;2020:6320514. doi: 10.1155/2020/6320514. PMID: 32733969; PMCID: PMC7378608. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7378608/

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2020/6320514

* This blog is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.